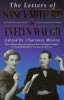

The Letters of Nancy Mitford and Evelyn Waugh

From Kirkus Reviews

From Kirkus ReviewsTwenty years (1946-66) of reciprocal, unconditional support between the twin sensibilities and manifestly unlike personalities of Nancy Mitford and Evelyn Waugh, expressed in a private shorthand of shared history and coined language. Mitford, refreshingly, ``can never take [her]self seriously as a femme de lettres'' or anything else; Waugh, depressive and dyspeptic, finds her characterological happiness ``entirely indecent,'' and her punctuation ``pitiable,'' but convention is hardly her strong suit. Or his. They write about writing (especially their own) and about politics and economics and money- -Waugh unbendingly conservative, Mitford flexibly socialist (``All the poor people in the world & so on. It's terrible to love clothes as much as I do''). But chiefly they write about Society, exchanging news of scandals and slights in their overlapping circles, peevishly keeping tabs on their pets: Cyril Connolly, a.k.a. Smartyboots or just S. Boots; Diana ``Honks'' Mitford Mosley, the fascist sister; Lady Diana ``Honks'' (also) Cooper and husband, Duff; Jessica ``Dekka'' Mitford, the communist sister; cousin Randolph Churchill, not always ``on speakers'' with Nancy; ``Prod,'' her mostly absentee husband, Peter Rodd; the ``Colonel,'' her mostly absentee lover, Gaston Palewski. Their common references can be suffocatingly precious or jarring--they consistently consider Jews a breed apart. Their contrariness bonds them at least as much and makes for better material: Mitford is a passionate expatriate who settles in France after the war and sprinkles her letters with idiomatic French; Waugh is a resolute Francophobe who tolerates America (which she abhors); he's a father, she's childless. Withal, they seek each other's counsel and salve each other's loneliness irreplaceably. Editor Mosley (wife of Mitford's nephew and editor of Love from Nancy, 1993) orders their high gossip appreciatively and authoritatively, contributing conscientious footnotes, welcome biographical apparatus, and the admonition that the whole correspondence is ``to be read as entertainment, not as the unvarnished truth.'' Best in controlled doses. Quite the battle of wits.

The Atlantic Monthly, Phoebe-Lou Adams

Mitford's niece by marriage, Charlotte Mosley, explains that she has omitted Evelyn's earliest letter to Nancy, "because it would necessitate thirteen footnotes in as many lines of text to explain people who do not reappear." She also warns readers, "Their letters were written to amuse, distract or tease and should be read for entertainment, not as the unvarnished truth." With those points in mind, a reader who enjoys malicious gossip and extravagant prejudices can get much pleasure from the Mitford-Waugh letters. Reading them is rather like panning for gold. In the midst of much water and gravel one finds sparkling phrases, glittering anecdotes, and now and then a nugget, such as Waugh's observation apropos Jessica Mitford's book on California funeral customs that the features "that strike us as gruesome can be traced to papal, royal & noble rites of the last five centuries." There is also an argument about how Mitford, in a piece on French affairs, had described the activities of a Catholic clergyman. Waugh, a niggling pedant on official procedure, was determined to set her straight. Mitford defended her sources. The reader gradually realizes that neither of them knew exactly what had gone on and therefore both were soaring in Cloud-Cuckoo-Land. Since they shared a detestation of the twentieth century, they were really more comfortable up there. Ms. Mosley's notes on the letters are terse and practical. One learns who the people mentioned were, whom they married (usually several spouses), and when they died. Occasionally one learns a bit more. Osbert Sitwell wrote Waugh a congratulatory letter about Brideshead Revisited but privately told friends that he found the novel "unspeakably vulgar." It is not safe to skip anything in this peculiar correspondence, but not advisable to read it straight through. The letters require the free time they originally had to create the effect that the writers intended.

<< Home